In December of 1946 a film hit U.S. theaters that told a story of a world trying to hold on to love in the aftermath of war, in which a celestial emissary came to Earth to aid a man caught between life and death.

Not It’s a Wonderful Life, but Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death , set in the final days of World War II.

While there’s nothing explicitly Christmassy about Life and Death, it makes for an interesting pairing with Wonderful Life—and in that film’s 130-minute running time, only about half an hour is specifically set on Christmas Eve.

It’s a Wonderful Life begins with a tableaux of a small town on Christmas Eve night, its citizens all tucked away in their garlanded houses, all praying for one man, George Bailey. The prayer range from little kids at bedside to Protestants speaking directly to God to Catholics invoking Joseph, Mary, and Jesus on his behalf. We’re in a Christian world, on one of that religion’s major holidays. Having begun in small-town America, Capra pans up to the stars, which begin zipping about and speaking to each in American-accented English. The stars are Joseph, a “Senior Angel” who is called Franklin in the screenplay, and Clarence, Guardian Angel, Second Class. I always assumed that the Joseph here is the Joseph, Jesus’ step-dad—but on re-watching the film I noticed that Joseph refers to this Franklin guy as “Sir.” I would assume that all three notable Josephs—Rachel’s firstborn, Mary’s husband, and, um, “Of Arimathea” would all outrank anyone born late enough to be named Franklin? So this Joseph must be some other guy.

It’s worth noting that we’re in a universe where an angelic bureaucracy sifts through the prayers, and seemingly decides to act when a certain quota is met. It’s also worth noting that earlier in the film, when George prayed for guidance in the bar, he was met with a sock in the jaw. This is, again, in a universe where prayers are at least heard, if not responded to. So was he left alone in that bar intentionally, to push him to rock bottom? Or did Joseph and Franklin just miss that one? Is there a Heavenly Intern somewhere who’s frantically deleting all records of that prayer so that Joseph won’t realize that this whole mess could have been dealt with earlier?

Oh man, I’ve fallen into a serious theological/worldbuilding pit here, sorry.

My larger point is that this film grounds itself strongly in a sort of saccharine, explicitly Christian, Americana. As much as I believe that It’s A Wonderful Life is a nigh-socialist image of working-class people working together against the rich for a better future, there also isn’t any room in Bedford Falls for even a Jewish or Muslim family, let alone a Buddhist or an atheist. The film gives us a universe where Christian worldviews are affirmed at every turn. So what we’re given here is a goopy story of a universe that really cares about us, angels who bingewatch human lives, prayers not just listened to but answered, a direct line between small town Pennsylvania New York and Heaven.

When I watched A Matter of Life and Death for the first time, I was struck by its similar opening: it also begins by sweeping over the universe. An unnamed, but seemingly omniscient male narrator talks us through the wheeling stars and novas like a particularly droll planetarium announcer. “This…is the universe,” he says. “Big, isn’t it?” He talks us through galaxies and novas as the camera slowly pans through the stars, making Earth’s minor place in the cosmic scheme painfully clear when he finally allows the camera to zoom in on our pretty little planet. At no point does the narrator introduce himself, speak to any other beings, or imply that he’s anything other than the narrator of the film.

And here’s where we diverge sharply from the sentimentality of It’s a Wonderful Life. We’re in a vast and seemingly indifferent universe. There are no comforting angels—instead we hear Churchill and Hitler screaming on the radio. And there are no earnest prayers rising up to us through the clouds, because once we reach Earth we start falling down, into the fray, hurtling through the stratosphere until we finally come to rest with an American radio dispatcher in England, June, who’s speaking to one Peter Carter.

When we meet Peter Carter, he’s getting ready to die. His aircraft has been hit, his fellow soldiers have all either died or bailed out, and he’s about to bail out, too, but there’s a catch, you see—he gave the last parachute to one of his men. He’s bailing out because he’d “rather jump than fry.” He doesn’t talk to God, or invoke any saints, he just talks to June. And he doesn’t speak like the British airman he’s been for the last five years, but like the poet he was before the war. He tells her he loves her (“You’re life, and I’m leaving you!”), gives her a heartfelt message to send on to his mother and sisters, and quotes Walter Raleigh and Andrew Marvell: “‘But at my back I always hear / Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near; And yonder all before us lie / Deserts of vast eternity.’ Andy Marvell—what a marvel!”

He asks her what she thinks the afterlife is like, whether they have props or wings (“I hope they haven’t gone all modern”) but she rejects the question as silly. She wants to find a way to help him—a solid, corporeal way. And of course this conversation could have been silly, or maudlin, but what June doesn’t know, but the audience does, is that Peter is splattered in blood, some his own and some his friend’s.

The camera shows us that Peter is sitting next to the body of his fellow airman, Bob Trubshaw. After Peter signs off he tells Bob he’ll see him in a minute, but the camera gives us a long, lingering close-up of the face of Bob, eyes shocked wide open in death.

The film may allow for whimsy and love, but there’s no sentimentality here.

Peter bails out, and wakes up on a beach. He thinks he’s dead at first, but once he realizes that somehow, miraculously, he has survived his jump and landed near June’s boarding house, he darts off to find her. We’re never told how Peter evaded death. The non-medical explanation is that his “Conductor,” number 71, missed him in “the accursed English fog” and failed to usher him off to the Other World—which is why he begins appearing to Peter and demanding that he shuffle off his moral coil already. The more rational explanation is that his visions of the Conductor are the result of a severe concussion. The film splits into two tightly woven threads: one in which Peter is fighting a cosmic battle for his life, and one in which he’s having seizures and needs experimental neurosurgery. The film gives pretty equal times to both of these plots, with fascinating results.

In the fantasy thread of the film, we once again have a Heavenly bureaucracy that is capable of screw-ups. Apprised of his mistake, the Powers That Be send Conductor 71 down to Earth to retrieve Peter, and one of the most striking elements of the film becomes clear: The Other World is in beautiful, pearlescent black and white. It’s all clean lines and ticking clocks, efficiency and pressed uniforms. The wings—we never see any props—come off an assembly line, shrink-wrapped.

But when Conductor 71 descends back to Earth, we’re presented with a glowing world of riotous color. The good Conductor even comments on it, breaking the fourth wall to say “One is starved for Technicolor…up There!” This is no bumbling Clarence, on the contrary, his Conductor is suave, debonair, a dandy who lost his head during the French Revolution—and still has some rather strong feelings about that. A quintessential Frenchman, he takes one look at June and agrees that Peter should stay—but he has a job to do, and that job is getting Peter to accept his death and come along to the afterlife.

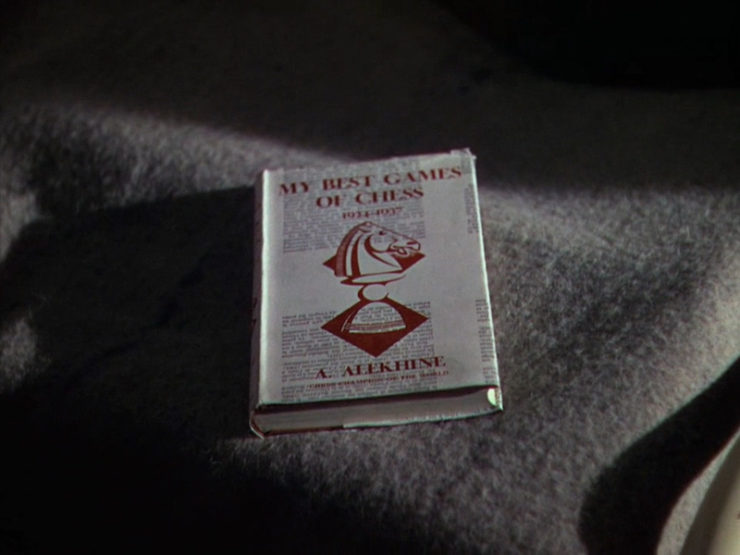

He threatens and cajoles, offers a game of chess, and later is even self-interested enough to try to trick Peter into coming back with him. And, granted, Clarence does have his own wing-earning agenda, but he also repeatedly says that he likes George, and wants to help him. He’s on George’s side. During the opening reel of George’s life, Clarence even brushes away mentions of Harry and Sam Wainwright, impatiently asking Joseph to get back to George, the real star of the show. Clarence is a humanist—though he probably doesn’t have the vocabulary to describe himself that way. Conductor 71, for all his foppishness, is also Other—frightening in a way that sweet, comforting Clarence is not. You believe that Conductor 71 is death. He is not on Peter’s side. There is no angelic army arraying to help Peter live. Peter’s an inconvenience, a blot on a perfect attendance record. In the vast configuration of things, he may not be a scurvy little spider, but he’s not important, either.

Once Peter learns what’s happened to him, and that he’s expected to leave life after all, he decides to appeal his case. But despite stating his membership in the Church of England in the opening scene, he doesn’t invoke any religion, he doesn’t pray, he doesn’t ask God or any saints or boddhisatvas to intervene on his behalf: he simply states that he wants a fair trial to state his case.

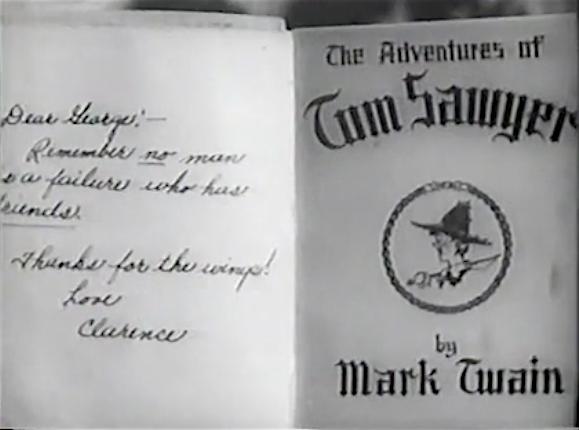

Compare with the goopy sentimentality of It’s a Wonderful Life. Clarence is presented as having “the IQ of a rabbit”—Joseph’s words, not mine—and his childishness is underlined by the fact that he’s reading a boy’s adventure story, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Clarence has already been passed up for promotion multiple times. (Like, how many people have died on his watch?) The elder angels are all worried about his ability to do this job, but they take a chance on him. Clarence stops George from killing himself by jumping into the river (which, I still don’t understand how that works—is the water only resistant enough to kill you if you want to commit suicide? Was George planning to allow himself to drown? Because that requires a whole other level of intentionality.) and finally succeeds in the end by asking Joseph to intercede and zap George out of existence. And true, this is his own idea, but it’s his only idea.

Here’s what A Matter of Life and Death could have been: Heaven messes up, and allows a doomed man to live. Doomed man falls in love, and then makes the case to Heaven that he should be allowed to stay. They debate the case, maybe with some Heavenly Head Honcho making a cameo appearance to tell them that, in the end, all that matter is love.

Instead: Life and Death never refers to its afterlife as Heaven, only ‘The Other World’ where records of every human are kept—“Russian, Chinese, black or white, rich or poor, Republican or Democrat”—and the one moment when young Richard Attenborough (!) refers to the place as Heaven, he receives a startled look from one of the otherworldly clerks. The film refers to its messengers as “Conductors” rather than angels. The two supreme authorities we meet are the woman who checks everyone in, and the man who judges the case at the end, but we never get any indication that these are godlike figures, or saints from any tradition. The film goes out of its way to pack the trial audience with people from a variety of backgrounds and nations, and repeatedly chides both England and America for their treatment of Indians, the Irish, Black citizens, Chinese citizens—basically all the people who have been oppressed by the two major powers represented by Peter and June. The film uses the trial not just to extol the power of love, but also as an indictment of empire. Where It’s A Wonderful Life creates a pocket universe where men march off to war and come home heroes, and where bank runs can be solved with common sense and decency, it’s bracing to see a film that goes out of its way to tackle national events as part of its arc.

Just as importantly, the film is relentless about giving realistic, plausible explanations for everything in the film after Peter’s inexplicable survival. Peter is, essentially, a mystic. Just as he seemed entirely confident in an afterlife in the opening scene, he accepts Conductor 71 for what he says he is: a messenger from the afterlife. He never considers him a hallucination, and he expects June to believe in the Conductor’s reality as well. June is understandably freaked out, and calls in an assist from her friend, the neurologist Dr. Reeves. So the film unfolds along two narrative arcs: Peter’s mystical trial in the Other World, and a starkly realistic medical drama in this one.

The film holds itself back from declaring anyone correct. Every single time it comes close to tipping into full acceptance of Peter’s visions, it twists the knife and gives us a rational explanation for them. One scene in particular struck me the first time I watched the film. When Dr. Reeves, seemingly offhand, asks, “Tell me, do you believe in the survival of human personality after death?” Peter’s response is not a simple yes or no, but, “I thought you said you read my verses.” June, level-headed and in-the-moment, replies “I don’t know, er, I’d never thought about it, do you?” and Reeves’ intriguing reply is “I don’t know, I’ve thought about it too much.” (Same, tbh.) So we have here a trio that represents a spectrum of spirituality: an Oxford student in the 1940s who is writing mystical poetry that addresses questions of meaning and afterlife—not the most popular topic in poetry of that time, by the way—a young American woman who’s too busy living life to worry about what comes after it, and an older British man who is willing to say he just doesn’t know.

This is already a far murkier world than the straight-ahead Christianity of Bedford Falls, and I simply can’t imagine a scene like this playing out in a U.S. film from the same era. Or, actually, I can—in The Bishop’s Wife, released the following year, the character Professor Wutheridge is initially presented as a highly-educated, somewhat curmudgeonly agnostic. Except his best friends are an Episcopal bishop and said bishop’s devout wife; he buys a Christmas tree each year; he decorates said tree with an angel; the film takes place in a world where an objectively real angel befriends him; by the end of the film he’s begun attending church again. So much for agnosticism, or even intelligent conversation across belief systems.

Where It’s A Wonderful Life runs full tilt into the gooey sentimentality of Clarence talking directly to Joseph, knowing that his every move is being watched by the Divine, A Matter of Life and Death gives us the clear reason of Dr. Reeves explaining that Peter’s visions are hallucinations—but that he has a better shot at surviving if everyone encourages his delusion.

And in the end, the mystical reading of both films hinges on books. In Wonderful Life, Zuzu, giver of petals, finds Clarence’s copy of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer on their tree, and hands it over to George as the bell rings. She, Mary Bailey, and George all see it. The reality of this book, which has no reason to be in the Bailey home and bears Clarence’s signature, stands outside of the arc of film and acts as proof, a preemptive strike against people who would trot out their “actually the end of the film is flashing before George’s eyes while he drowns” arguments.

In A Matter of Life and Death, it’s a book about chess moves. Conductor 71 borrowed it from Peter after he offered to play Peter for rights to his life; in the “real” Technicolor world, the book has not been seen since. During his surgery, Peter imagines the Conductor tossing the book back to him, and a scene later, June finds the book in Peter’s jacket pocket and packs it into his suitcase. She has no knowledge of conversation with the Conductor, and doesn’t think finding the book is odd. And indeed, it might not be. It’s possible that Peter’s fevered imagination remembers this as the one last loose thread, and returns the book to himself, knowing that he’s simply left it in Dr. Reeves’ house.

The comfort to be found in a film like It’s A Wonderful Life, and one of the reasons I think it’s so popular, is not only that it affirms the idea that a “simple” life is important, but that there’s a larger cosmic structure that keeps track of the simple lives, and cares about all the small nice things people do for each other. The moment that Clarence really starts to like George is not when young George stops Mr. Gower from accidentally poisoning a child, but the moment a scene later when he learns that George never told anyone. Only Mr. Gower, George, and all these various Recording Angels know of George’s true heroism and decency, and it’s that idea that attracts people. How many tiny acts of kindness, mercy, generosity have you committed over the years, and never told anyone, never expected any thanks? (spoiler alert: I have not done enough.) Here’s a film that’s telling you that they were noticed and appreciated.

A Matter of Life and Death offers a very different comfort. In the end it says that even on a tiny planet in the midst of a teeming and largely uncaring universe, the love between two people can be important enough to force Heaven to change its plan, and bring a man back to life…OR that even in a rational, clockwork universe, without a Recording Angel in sight, that heroism exists in the form of scientists and doctors working tirelessly to save a man’s life, and that true love can help people fight even the worst medical disaster.

Why am I proposing this as your next big holiday tradition? Originally it was because I noticed these odd spiritual parallels between Life and Death and Wonderful Life. Then I learned that it was actually released as a Christmastime film here in the U.S. But those are just fun, coincidental ribbons on my real reason: I love this movie. I want to share it with everyone I meet and everyone I never meet because, like many of the best holiday movies, it insists that there is magic to be found in this world. But if you’re looking for a break from the sappy didacticism of It’s a Wonderful Life, Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death keeps its miracles ambiguous, hard-won, and sometimes, even, gloriously secular.

Leah Schnelbach think about Peter Carter’s opening monologue Every! Single! Time! she gets on a plane. Come, quote Andy Marvell at them on Twitter!